[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Blog Overview:

In this article, we’re going to answer the following easement law questions:

- What is an easement?

- What types of easements are there?

- How is easement law applied?

- What remedies are there for easement infringements?

If you have a question about an easement affecting your business, contact our specialist commercial property lawyers today. For easements on rural land, our experts in buying rural property can help. Read on for information relating to residential easement issues.

What is an easement?

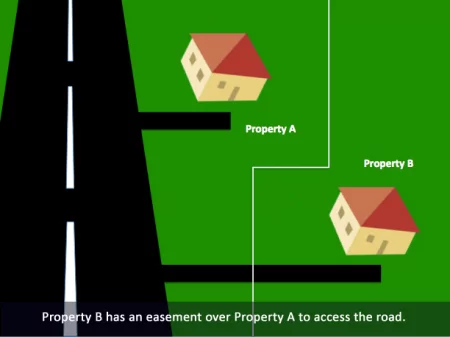

So, let’s start at the beginning: what is an easement? At its simplest, an easement is the legal right to use someone else’s land for a specific purpose. Imagine, for example, that your home has no access to the street except through your neighbour’s property. You would need an easement to use a driveway-sized strip of land to come and go from home. Without that easement, your lovely home would quickly begin to seem rather prison-like.

Easements NSW

Now imagine how this old English easement law comes into play in a very hot property development market, like Sydney. Things stop being simple, and the risk of easements litigation becomes very real. Modern types of easement cover things like:

- Rights of way (similar to the driveway example, but also including walkways or pathways);

- Public utilities, such as gas, electricity or water and sewer mains;

- Parking areas;

- Access to light and air; and

- Shared walls.

An uncooperative neighbour or an adjoining property owner with an adverse economic interest could ruin the value of a sizeable financial investment.

Understanding easements & avoiding easement litigation

First, a bit of easement law – the land that benefits from an easement is generally referred to as the “benefitted” property (the land without access to the street, in the example). The property that gets no benefit is referred to as the “burdened” property.

An easement contract creates a property right, for which the benefitted party must generally pay the burdened party. A burdened party may refuse to grant a private easement. The easement, when successfully negotiated, should be recorded in the Land Titles Office, just as the deed to property should. These are called registered easements. Statutory easements, like those for electricity or water, need not be recorded.

In rare circumstances, where land has been used for a particular purpose for a very long time, as a pathway for example, courts may imply the existence of an easement. In other situations, where the granting of an easement is seen as necessary for the public interest, health or safety, a court may order the creation of an easement.

A property easement is not a personal right, but attaches to the land. It is usually included in the title. Ownership of the property does not change hands, however, just the right to use it for a restricted purpose. The purpose may be quite narrow. It would be a mistake to assume that an easement which permits a benefitted party to park a car on burdened property implies the right to build a garage.

Someone seeking an easement to use adjoining property for customer parking – a parking easement – to ensure that an adjoining landowner does not construct a building blocking a view, or for any other purpose should:

- be prepared to negotiate and pay for the right;

- record it immediately; and

- use the land only for the purpose specified in the easement.

Someone who is buying property should check land records for any easements that exist. Every landowner should also ask about the existence of any easement agreement before beginning construction or any major renovation of a property.

A benefitted party has the obligation to maintain the easement, ensuring for instance, that a parking area is kept in safe condition, although this may be negotiated by the parties. A burdened party may not interfere with the intended use of an easement by, for example, putting a chain across a right of way.

Easement law: remedies when an easement is infringed upon

Either the benefitted or burdened party may come to feel that the property right granted under an easement is being infringed upon. Two courses of action present themselves.

In theory, either the benefiting party, whose right to make use of an easement has been infringed upon, or the burdened party, who believes the right granted by the easement has been exceeded, has a right of abatement. The party exercising this right must demonstrate that there was no breach of the peace, no harm to the public and that only reasonable force was used. Courts, however, frown on anything exceeding minimal self-help. An aggrieved party may also sue for damages, nuisance or seek an injunction. The latter choice is recommended.

An easement may also be removed with the consent of both the benefited and burdened parties. The agreement to remove an easement should be documented by a solicitor or a registered conveyancer and filed in the Office of Land Titles. In certain circumstances, an easement can be removed from the title by a court if it is no longer used or needed.

The attorneys at Owen Hodge Lawyers would be happy to offer legal advice with regards to any issues you may have in either negotiating for an easement, in registering or removing it, or in litigation arising from an easement dispute. Speak to the experienced property lawyers Sydney residents trust on 1800 770 780 to schedule a consultation.

You might also like:

- Electronic Property Transfers Come To NSW

- Pros & Cons of Purchasing Commercial Property

- Buying Property Off The Plan: Risks & Protection

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]